This post is subject to editing, because I don't know if I'm getting my point across or not.

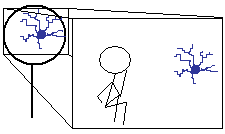

It felt roughly like this. I don't know why it looks like a tumour. Also the feeling was slightly outside my skull.

I knew I was being conditioned because I noticed my natural reactions getting changed. (Sadly, I forget which reactions.) I knew it was due to highly impressionable psycho-social development because the feeling of being conditioned was very similar to the feeling of thinking about dealing with the other students.

I still wanted good grades (foolishly) but rather objected to being conditioned.

So I willed it to stop. I recalled the feeling of the network, and added the idea of eye contact to get it to sit up and pay attention. I imagined myself telling it to shut down. It did.

Once I escaped school, I needed to get it to wake up again.

I repeated the recall image and then nudged it awake.

It turns out you can in fact delay developmental benchmarks if you want. The downside is you need to know, as a stupid kid, which benchmarks to play around with. I got lucky with this one, I broke some things playing around with this.

24 comments:

Almost everything we believe, we believe on the basis of authority. This applies even things that are subject to empirical falsification. (I have, for example, never actually performed the double-slit light experiment. I've seen it done, but I could've been a trick.)

Humans are therefore very stoutly wired to receive programming from authority. And this works more or less okay most of the time, because the authority (in the adaptive environment, parents, extended family, tribal elders) is trustworthy. By trustworthy I mean not necessarily expert, but merely having no ulterior motive to mislead.

Mass education, i.e., mass programming by authorities unlikely to be related to you, is (and always has been and in fact cannot not be) about creating a compliant and productive workforce.

The ability to turn off "psycho-social development" is probably a bug, which for most of human history would have been purely maladaptive, but which because of this artificial mass-schooling experiment, turned out to be beneficial (I suppose) in this case. That doesn't mean, of course, that it isn't long-term maladaptive. You are right to try to get it to turn back on.

It may be that the best you can do (and I think many in the reactosphere are like this, I certainly include myself in the camp) is consciously acknowledging a psychological handicap and making the necessary, even if uncomfortable, adjustments.

The fish who knows he's wet suffers to some extent from that knowledge. But it's still better than trying to live out of water.

It's probably based on the placebo effect.

> And this works more or less okay most of the time, because the authority (in the adaptive environment, parents, extended family, tribal elders) is trustworthy.

> The ability to turn off "psycho-social development" is probably a bug, which for most of human history would have been purely maladaptive

Well... What you say about the traditional society is utterly important, but you exaggerate the harmony of that society. While I am no pure sociobio reductionist about human nature, it's a key lens to be sure. It tells us in plain terms that other people/organisms are most certainly trying to manipulate you very markedly, even within the most pristine and natural human society -- as in any society or congeries of any organisms. In fact, this is markedly true even within the immediate family, where there prevails the strongest harmony of all (save that between identical twins). Sibling rivalry can be pretty bad in human beings ; in some taxa, however, it regularly goes much further than it does in man. Then too, it's been claimed human mothers direct a higher solicitude to better-looking babies, because of their higher fitness-value -- though one should bear in mind that at least half of peer-reviewed publications in fields softer than phys/chem are not replicable. (My feeling is 75-85% are false depending on the field. There is of course no fine line between chem and bio, and surely most of the stuff in J Biol Chem is true.)

Far less in doubt, there being endless publications on it, is gestational diabetes, in which the fetus, the mother, and the father's genetic material are in a fairly pitched struggle over how big the baby will be. (The father and baby 'want' the baby to be rather large even at considerable risk to the mother ; though they certainly want the mother to survive unharmed, this is less of a priority for them than it is for her.) Over the population as a whole, the total morbidity from gestational diabetes is rather considerable.

As for very old people, they tend to be -- relatively -- disregarded by their close kin, because they have zero potential for direct reproduction of shared genes, and little/decreasing potential to assist indirectly with such reproduction. (Just as people feel more solicitude for young kin than 35-40ish kin, ceteris paribus.)

The amount of conflict (nonharmony) of course gets markedly higher as you move to the extended family, and then to the old-school traditional society, the trad-imperial society that first emerges perhaps three or four millennia back, followed by the bureau-society, and finally the rather distinctly alienating late bureau-society.

Even in a traditional society, someone has to be the ultimate temporal authority. That person will have to self-lead.

"in some taxa, however, it regularly goes much further than it does in man."

Which taxa? Do you mean they murder each other?

"Then too, it's been claimed human mothers direct a higher solicitude to better-looking babies"

Everyone is biased toward treating the better-looking better, because 'easy on the eyes' translates to 'easy on the consciousness.'

"My feeling is 75-85% are false depending on the field"

Somewhere around the time I was messing with my psychosocial development, I was reading New Scientist and trying to teach myself to vet studies on instinct. I would guess whether one was correct, and test it based on later, contradictory studies. Your estimate is correct based on my sample.

(The training worked.)

I have a link independently verifying this for medical science. (Paper.)

[...] Accordingly, conditionability in man is more sophisticated, variable (over individuals), and dynamic than you suggest.

And it's not just (trust)worthiness that enters into the equation: power is probably a stronger factor. When in nazi Germany, most people do as the nazis do. When in prostrate antigerman late-bureau Germany, most do as the prostrate antigermans do.

Of course, that's not at variance with what you are saying, since you agree power is as important as worthiness today. But while we would agree that power has recently enjoyed tragic gains relative to worth, I say power was, in many places, about as strong a factor of conditioning-receptiveness as worth was, even many centuries ago.

I guess my chiefest picture of the 'almost-alienly unalienated' society comes from Rousseau's Confessions: France, Switzerland, and Italy on the eve or fore-eve of 1789. While I am not in the slightest doubt about the essentially post-lapsarian nature of that world, and though Rousseau in particular had plenty of good fortune, it seems extremely inviting.

The Ioannadis paper had a lot of publicity. Had me a look when it came out. I am too weak to follow the math, but I too know something about such things from simply looking at large numbers of contradictory publication abstracts.

Even with little science background, anyone can have a look at the 'embarrassed fields'. I believe Ioannidis mentions 'cancer genetics', but 'behavior genetics' is just as bad -- nearly a total wasteland. Granted these are young fields.

Also their names can be misleading to the nonbiologist. We know tons and tons of (true! replicable!) stuff about the genetics, or at least the geneticity, of behavior (and cancer) -- from twin studies, and perhaps also from pedigree(?) studies (not sure what the proper term is). But to the best of my understanding, that is not usually embraced under the term 'behavior genetics', or at least twin studies aren't.

Blah blah aside, my point is we know tons about the heritability of behaviors, yet almost none of the papers about individual genes are replicable (as of five years ago anyway).

> Everyone is biased toward treating the better-looking better, because 'easy on the eyes' translates to 'easy on the consciousness.'

Easy on the ol fitness, in more ways than one. --Be they kin, or nonkin who are allies or potential allies.

Also, when I went to look at the papers that failed to replicated or pairs of contradictory papers, there were always several glaring methodological errors.

In other words, how to do better is already known.

McIntyre's findings about Mann's scientific deficits are presented as surprising and unusual. They are neither, indeed Mann is slightly more diligent than the average paper-writer.

The basic problem seems to be that journals don't know or don't care what science is, and repeatedly accept abysmal examples of pretend-science.

I don't really go to climate land at all, since I have just a hint of stats (no schooling), and no diffEQs at all. A year of physics at a good college, but I don't have a rapport with it beyond classical mechanics.

I never even understood what an electromagnetic wave IS. I mean, it's force, right? -- a disturbance in the EM force field in -- classically -- 3-space. But how far -- perpendicular to the wave -- does the force extend in 3-space? Does the force fall off as distance squared? I could have been busy looking at pretty girls, but it seems to me they never explained this elemental stuff, and so I was always just fundamentally buggered on EM waves. A sound wave is another matter, I think I grasp exactly what it is.

The first didactic question is of course, why should I care, instead of look at pretty girls. In high school they never really said why mRNAs or proteins matter, so I steadfastly paid no attention. They just implied it was truly important, which doesn't seem to be good enough for me. If they said at the very beginning that the seeming wilderness of biology was in fact quite tractable on some level, because there are only four basic macromolecular classes (plus small molecules), and in a pretty strong sense only one among them (proteins) really 'does' anything, and the basic nature of proteins is entirely uniform and comprehensible across the whole diversity of ~(?)200,000 protein species that make a primate what it is -- I would have been pretty interested.

(There are a few times, or several times, more protein species than genes, if you count every minute variant that occurs in fully-processed proteins.)

Being a kid, I had no concept that anywhere near such a powerful handle on organisms existed and could become quite comprehensible to me. How was I supposed to know that? For all I knew, the vigor of fundamental biological knowledge was 10x lower than that -- or perhaps 50x, in which case why bother. Even though it was an elite high school, they never told me that, so I chose to contemplate:

1. heartbreaking sweet faces

2. breasts

2a. aureoles

3. bras/ tight shirts

4. beautiful locks of hair

5. pubises/genitals

6. panties

7. legs

8. arms

9. napes

10. earlobes

11. the concept of god

Conventionally, all particle-waves extend throughout all space. (I suspect this is an idealization that makes the math easier, like assuming space is Euclidean when convenient.)

Yes, EM wave forces fall off with r^2.

So you know how a changing electric field induces a magnetic field and vice-versa? How generators and motors work? The math works out that this induced field can be self-sustaining. That's all that a photon is. Indeed, every changing EM field will throw off photons at the edges. This means motors and generators inherently give off light.

If I'm not being clear, I'm happy to try again and again until I am. Same way I eventually managed to communicate with Spandrell.

"They just implied it was truly important, which doesn't seem to be good enough for me."

Quite. Indeed this is slight evidence against the idea. If it was truly important, you don't have to say so. E.g. nobody has to mention how important the heart is to circulation.

"I would have been pretty interested."

They would have had to know all that to be able to tell you, though. All they knew is their authority said it was important, so they said it too.

-

Nice list there.

> They would have had to know all that to be able to tell you, though. All they knew is their authority said it was important, so they said it too.

Yes, . . .

Yeah it has struck me again and again how simple it all is. Hydrophilicity. Lipophilicity. Amphiphilicity.

Shared electrons: the covalent bond... makeable, breakable

the distribution of (infinitely fine degrees of) electrostatic charge over the surface of a molecule.

four classes of macromolecules, only one of which is both 'active' and diverse

the steric-electrostatic complementarity (or not) of molecules, that makes them stick on each other (or not)

the considerable flexibility of large molecules, and the ('intentional') impreciseness with which they fit together, changing shape a bit to accommodate each other -- which change of shape causes them to become complementary with, and indeed bind with, further molecules that they wouldn't have bound with earlier.

That latter idea is the soul of biology. It (combined with the concept of energy input) explains why biology doesn't just 'stop'. If all the various molecules that can fit together, indeed do so -- and why shouldn't they, pretty soon -- then that would just be the end, right?

The 'soul' of bio, along with the other basic tractabilities of bio, should be covered in the first 20 minutes. With concrete examples of course. In fact, with models you can hold in your hand.

The 'soul' would not be that easy to understand, if you are a kid with a soft little head, but it's the ONLY thing that explains WHY you can "get from" some recoiling "billiard balls" and wads of matter -- atoms, molecules -- to a freaking organism. I'm afraid it's not something you are going to notice for yourself at age 15, whether you are smart or not. You need help. If you were kinda average, you would probably need to go over it about nine times.

But until you get it, there is really no point in studying the "billiard balls of life" -- organisms qua matter. It is a bunch of senseless blah blah. You could instead learn a little evolution, which is somewhat easier.

But as you say, the point is just to train you to deal superficially with 'whatever' -- with whatever some jerk wants you to deal with. Whenever.

> Yes, EM wave forces fall off with r^2.

> Conventionally, all particle-waves extend throughout all space.

Cool!! That's kind of what I thought should be true -- just like point electrostatic charges -- but it seemed odd. I leafed through the text some . . . but . . .

That they are commonly depicted as sinusoids is confusing to a dizzy gentleman like me . . . only in college did I say, oh, but they aren't sinusoid IN SPATIAL EXTENT, idiot . . . so then I'm all: but what ARE they like in space. Good to finally know.

How long are they? They must vary in length? I mean of course total length, not wavelength.

> So you know how a changing electric field induces a magnetic field and vice-versa?

Vaguely. But no, I'm only conversant with electrostatic charge and electric current. Magnetism = too hard/ not interested enough (thank you anyway, though).

"ONLY thing that explains WHY you can "get from" some recoiling "billiard balls" and wads of matter -- atoms, molecules -- to a freaking organism. I'm afraid it's not something you are going to notice for yourself at age 15"

Of note, many don't understand enough to even know there should be a problem.

"Magnetism = too hard"

This bit's easy. My numbers will be entirely wrong, but basically it works like this:

There's an electric field of one volt. The charge powering it moves away to infinity, so it drops to zero. This induces a magnetic field of one tesla. But the particle is now at infinity, and so the electric field has stopped changing, which means the magnetic field has lost its source. So it drops to zero. This induces an electric field one volt.

Now the magnetic field is gone. The electric field has no source. It drops to zero, inducing...

That's what I mean by the math working out. The M field induced by the falling E field is exactly strong enough to induce the E field again as it dissipates.

"How long are they? They must vary in length? I mean of course total length, not wavelength."

Photons? Depends what you mean. Like all quantum particles, its total size is basically a sphere centred on its creation point with a radius equal to how long it has lived times light speed.

However, 99.9etc% of its probability is often packed into a tiny space of little more than one wavelength sphere'ed. If you try to pack it down further it either gets absorbed or diffracts all over the place.

I think one reason physicists don't talk about the photon's size much is that they don't really themselves know. Since quantum interactions can get so hairy, it's hard to say what happens when a photon gets close enough to another particle that its fields have non-negligible impact. All we really know is that refraction is a result of the photon's EM field interacting with the substance's nuclear matter in much the way a classical EM physicist would expect.

Or put it this way: a proton will let you pin it somewhere and pull electrons toward it. However, not only can't photons be pinned down, by the time the electron is feeling a pull, the photon has reversed its field and is about to start pushing. Visible light has a frequency in the 10^14 range, so to measure an individual pull from a photon needs an instrument with resolution of at least 10^-15 seconds. You got any femtosecond force testers handy?

"That they are commonly depicted as sinusoids is confusing to a dizzy gentleman like me "

It's confusing to everyone who doesn't already know what it's supposed to be. The sinusoid is a 3D graph, the axes are time, E strength and M strength. Since c is a constant, you can convert the time axis to one dimension of space, conventionally oriented in the direction the photon is travelling.

From these graphs, you can see I simplified slightly. Actually the induced fields' strength depends on how fast the other field is changing, which means they both vary continuously. They might as well discretely swap places, though.

OK, I was picturing a discrete 'line segment' which might be, oh, a mm long, or ten feet, along which electric charge alternates sinusoidally from + to - to + to - . . . with the strength of electric force falling off, as r^2, perpendicular to the axis of the line segment.

So say it's ten feet long, and passes near some positively-charged object in a vacuum, at c. I was thinking the positively-charged object would experience first + then - then + then - electric force, and would thus be accelerated back and forth and back and forth, perpendicular to the axis of the EM wave. --But evidently that is not the right thing to be thinking.

So the wavelength can be defined wrt time, or wrt the spatial dimension of travel . . . is one more fundamental and proper than the other?

But there is, as opposed to wavelength, no 'length' at all? Just a probability density distro whose probability is almost all within some tiny space.

What's it like to understand all that heavy stuff ; can you understand any of Mitchell's ideas about consciousness? Can you understand stuff like the observer effect? I tried to read about it once, but as you can probably see, that amounted to dabbling in fancy stuff without having strong fundamentals -- or any fundamentals -- and accordingly I did not understand much of anything about the observer effect, even though I can dimly grasp basic aspects of the double-slit.

" is one more fundamental and proper than the other?"

They're exactly the same. Not really different, because wave velocity is independent of both, and v=(nu)(lambda). Speed is frequency times wavelength. This is true of all waves, I believe.

What I'm trying to say is if you know what kind of wave you're talking about, and you know one, you know the other.

-

"Can you understand stuff like the observer effect?"

Totally misnamed. Superpositions will decay even from internal thermal vibrations. They're incredibly unstable.

To observe, you must interact. To interact means to exchange energy; to exchange is to change. To change is to disrupt superpositions. (Almost always.) Then some crackheads called it the observer effect.

-

It may be that my understanding of photons is underwhelming.

But think about this: the way a microwave works is by rocking electrons back and forth along the aggregate light wave. It has nodes and such just like any classical wave.

It's just a question of what an individual photon's contribution is, and I think the answer to that question may be more complicated than I realize.

Yes, come to think of it, it is. So, two things.

Turns out physicists don't know the answer to your question. The photon is considered to be 2D - to have no finite volume. But that's okay, because electrons are points, with no volume either. So a single electron can see an electric field from the photon even though nothing else in the universe sees it.

I think that's a cock and a fraud. But let's do the second thing before I get into that.

Second, photons are bosons and do the whole Bose-Einstein condensate thing. You can't remove a single photon from a microwave, it has no individual existence.

And if you fire a single photon into the microwave in the first place, whether it acts more like a wave or a particle depends on the specifics of the measurement.

But anyway, the first thing. To get to a finite volume wave like a microwave, the photons must have some finite volume to add up to it, especially as we know that the photons number in finite values. I expect this point-thing is another simplification to make the math easier that's now biting us in the ass.

Second, photons form in a highly classical way. When you move an electron, the field can only update at the speed of light. So on the receding side, it forms a saddlebow. At roughly the point where the trough of the saddle reaches zero, the leftover field breaks off and goes waving off into the distance.

This field is instantiated in photons.

Unless you only have one photon, in which case quantum effects - the fact that energy has to move in chunks - causes weird destructive interference, and the entire wave moves off as a roughly spherical packet that's really small.

But since physicists don't understand this, I can't offshore the mathematics and thus don't know the details.

I could try to guess, but again due to h-bar, to have the photon try to push an electron around would more than likely just result in the electron absorbing the photon. It can't absorb half of the photon, which means there's no transfer of energy, which means transparency.

So with individual photons, all I can really tell you is what they're likely to be absorbed by, which is their wavefunction. Still, the wavefunction will be roughly the size of the electric field, due to the fact that the Schrodinger equation takes the field as an input. If you look it up on La Wik, note the Hamiltonian includes V, which is simply the classical energy fields.

I dunno. Is this helping? I feel I'm kind of losing threads and grasping new ones.

-

"What's it like to understand all that heavy stuff"

I need to know what it's like to not understand it as a baseline. So what's that like?

This question has been brought to you by Socratic Irony.

-

Consciousness in a sec. Have to look up what you mean.

Time for edits using deletion!

Sweet video about microwaves I should have linked above: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kp33ZprO0Ck

-

He believes in UFOs, but I can't find anything concrete on what he believes about consciousness. I suspect that Mitchell hasn't realized that even Mitchell doesn't really know what Mitchell believes about consciousness. At least, he doesn't have any beliefs with anything like the detail necessary to apply specifically to consciousness as a real thing in reality.

This is an epistemic principle I think is worth having some detail about.

Reality is really complicated. If your ideas about reality are not complicated, then they're (usually) not about reality.

This is fine if we're talking about TV shows or other hypothetical worlds.

But Mitchell's ideas about consciousness can't be correct simply because they're not sophisticated enough. When we make a prediction from them, it will only ever come true due to chance, or quite possibly never. Because the ideas are so simple, we can't tell if the predictions that are kinda-sorta okay are off because the model is wrong or because the model is missing bits. Would it work out okay with those bits in? The only way to find out is to add the bits. And if I add the bits, it won't be Mitchell's consciousness theory anymore, but mine.

Most subconscious minds are smart enough to roughly grasp this. Therefore, Mitchell does not believe these things because he is attempting to understand consciousness. It is for some other purpose I don't really know.

Of course this is all highly sensitive to further inquiry, data, or being informed.

In future, I would recommend giving me a specific idea, theory, or prediction, rather than naming people. I won't know the named fellow, most probably.

> He believes in UFOs

Really?

I've seen him engage in some 'ultraspeculations', but they were more or less meritorious.

Then too, I suppose I won't categorically rule out the existence of human knowledge of intelligent aliens, even though it seems like a pretty vanishing chance. So many people will drone aprioristically about conspiracy/secrecy, without noting that at least a few high-salience secrets do seem to have been held by quite large bodies for at least a couple decades.

Although thousands of people were involved in the deciphering efforts, the participants remained silent for decades about what they had done during the war, and it was only in the 1970s that the work at Bletchley Park was revealed to the general public.

I don't know, perhaps one could argue there was limited motive to breach the secrecy of Bletchley.

I do strain to follow him on mind-body even when he's not employing advanced physics concepts, but with that caveat, I do not really see how you can find him simplistic on the question. De gustibus I guess.

He seems to have much the same concern as us, about science being so impressive that it tends to subtly alienate vast populations from consciousness/qualia and whatever else does not belong - at least not clearly - to naturalistic ontology. Jaron Lanier may have some rather comparable concerns.

> To observe, you must interact. To interact means to exchange energy; to exchange is to change. To change is to disrupt superpositions. (Almost always.) Then some crackheads called it the observer effect.

While that does make prima facie sense to me -- I mean Planck, uncertainty, ja? -- as a total ignoramus I won't say more than that.

Unfortunately I can't follow the rest of your latest remarks on physics at all.

"without noting that at least a few high-salience secrets do seem to have been held by quite large bodies for at least a couple decades."

If there was a really successful conspiracy, would we ever know? The men involved would take the secret to their graves. It's physically possible, which means it has probably happened.

Which means that what we know of conspiracies was learned by studying failed conspiracies. "Conspiracies always come to light." Failed ones do have that pattern, yes.

However, for UFOs in particular, I've never seen a theory of space aliens that was unfalsifiable, but the believer never wants to bring up the obvious tests...

"I do strain to follow him on mind-body even when he's not employing advanced physics concepts"

Like I said, I couldn't find anything concrete. Where can I go to read this stuff?

"Unfortunately I can't follow the rest of your latest remarks on physics at all."

As before, I'm willing to try again until it works.

If you're willing, I suggest picking one of the following paragraphs, I'll try to explain that until you get it or I run out of ways to explain it, and then move on to another. We should cut down on the sprawl. Of course you're welcome to make a counter-proposal.

Light waves act like classical waves most of the time. The problem is working out how the quantum adds up to the classical.

Physicists model single photons as a 2-D disc, and their targets as 1-D points. I don't think this works because the volume is zero and the intersection is zero. I think they do this because it makes the math easier, but will ultimately be found to be unphysical, much like Euclidean space.

Since physicists don't treat photons realistically, I can't exploit them to work out the math for me. I kind of have to guess what a single photon looks like. The guess I have is like ones that have been successful in the past, though. Ultraviolet photons can be fired like bullets, not aggregate together into a classical wave, and hit specific wavelength-sized targets. This means their probability distribution is tightly confined, which, since the Hamiltonian includes their EM field, means their EM field is tightly confined.

In a Bose-Einstein condensate, the particles become indistinguishable; the whole mass acts like a single particle. Low-frequency light does something very similar or identical. The math behind it shows that you can't factor out a single photon, which means the contribution of individual photons becomes indistinct.

> Like I said, I couldn't find anything concrete. Where can I go to read this stuff?

Mind-body is his main subject at less wrong recently - and perhaps also less recently.

If you have anything conveniently at hand, where does he talk aliens (or, Fermi paradox)? His 'large life/ small life' idea recently posted at less wrong could have some relevance to Fermi -- but it strikes me as 'worthwhile but prima facie weak'.

I assume the Bletchly people were given some cover story to preserve their honor and employability -- lest someone accuse them of having spent the war poolside in Acapulco. In that case, where's the motive to divulge?

--Therefore, I'll mention 'one and a half' other large and seemingly pretty well-confirmed conspiracies in 20C Italy: the aborted Borghese coup, which was only secret for about a year after its abortion -- and the Gladio/ Propaganda Due thing as a whole, which I think remained secret longer. It appears to have been a USG-sponsored govt-in-waiting -- waiting mainly on the possibility that avowedly Moscow-neutral 'eurocommunists' might corral enough power to withdraw Italy from NATO, and set her officially neutral to both NATO and Warsaw.

I have a vague memory of reading that many of the wikileaks diplomatic cables were accessible to quite numerous people. If so, it's of interest since the motive to divulge something (publicly) could have been considerable, or such is my guess.

Nevertheless I suspect most 'conspiracy-like' activity is accomplished rather amorphously, with low explicitude and high deniability: which is to say that it is not a conspiracy. An conspiracy does not obtain unless there is some XYZ that that would amaze people if exposed. If XYZ is too (complicated * deniable * diffusely-ambiguously-evidenced), it will fail to amaze, even though it be an amazing thing.

On the physics stuff, thanks for the offer, but I'm quite confident I won't be able to follow.

I see. I found a different Mitchell than the one you were talking about. Now I know to look at LW, do you mean this guy?

I can probably understand Mitchell. To verify I could ask him some questions.

He gets very close to where I went, but turning back at the last minute and not actually reaching the conclusion. It's a curious pattern.

What I said about vagueness applies to this Mitchell too, in the sense that he doesn't quite know what he wants to get at. It seems he wants it to be monistic, but isn't willing to take dualism seriously enough to understand it well enough to disprove it.

I think the commentators on his articles realize that his points lead to dualism, and this results in the downvotes. Because dualism is low status, and they're repulsed by it.

-

By the way, if you'd rather a less public exchange, you have have my email.

-

"On the physics stuff, thanks for the offer, but I'm quite confident I won't be able to follow."

We should do an experiment and find out. If you're right, you get proven right. If you're wrong, you learn something.

I should add that Mitchell, like many, have subconsciously grasped that quantum and consciousness are linked. However, they all seem to focus on maintaining or using superpositions -

"The quantum crosstalk is too weak to have any functional significance."

Instead of noticing that the opposite, the collapse of superposition, may be exploitable.

The idea of unconscious simulation of consciousness is wildly insane.

A consciousness cannot perform any action that an unconsciousness can't. However, the computation behind the action must be different. So the unconsciousness' acts will be statistically distinguishable from the consciousness'.

To act statistically identical, then it won't be simulated consciousness, it will just be consciousness. It's like a simulation of dynamite that can actually demolish buildings. It's not a simulation in any meaningful sense.

This is so much easier if you consider the consciousness might be dualistic.

I'm almost sure Porter spoke of functionalism as if it were a serious position, not that he necessary holds it. While nobody's perfect, I thought that was funny. When I look functionalism up in the Stanford Cyc. Phil., it is obvious to me that it's just a way of denying awareness. To paraphrase their spiel, awareness (eg pain) only exists in relation to propensities/behaviors, other qualia, etc. What nonsense ; hardly anything is more typical of awareness or pain than the fact that they are non-relative. They speak for and about themselves. They are exactly as direct and immediate, and exactly as deniable -- not very deniable at all -- as the sensory inputs from which we develop natural science ; that's the whole reason we have a mind-body problem.

What dualism do you like? Property dualism... implying perhaps at least a modest form of panpsychism?

To the extent that I have grasped your position (reading various of your posts at odd moments), you are no epiphenomenalist. In that case, as my favorite 'naturalist'/physicalist spiel goes, how do you answer the particle man? The particle in the cloud chamber obeys his predictions to a precision of, oh, 0.0000000000000000001. The particle man presumably hews to some emergentism re awareness which I think you are roughly as skeptical of as I am. But if you attribute any property, any duality, to the electron or any other particle, that he has not attributed to it, and that has any causal interrelationship with any of its other properties, then how come he defeats you in cloud chamber trajectory predictions (or doesn't he)? Does something happen in brains that simply cannot happen in cloud chambers?

I don't necessarily have a clear answer, myself. Porter said he sometimes finds the whole situation we are in 'impossible' -- or rather, illogical, since we cannot really be in an impossible situation except figuratively. I have entertained the hypothesis that the world is just brutely illogical -- except within certain broad limits which encompass commonplace life and thinking, as well as natural science -- and that beyond that quite extensive sphere, logic simply isn't true at all, and that is perhaps why mind-body cannot be solved. It's not clear to me how consonant that standpoint is with what Goedel said. I am aware that the incompleteness theorems are only proven for 'systems' (or something) that are 'stronger' than Peano arithmetic, but I have no idea how you find out whether some X is a 'system' that's stronger than Peano arithmetic. Also I wouldn't swear that I understand the theorems: they say strong systems are inconsistent OR incomplete, right? Like any old bloke I am flush with confidence that I quite understand what 'inconsistent' means -- not as sure about 'imcomplete'.

" What nonsense ; hardly anything is more typical of awareness or pain than the fact that they are non-relative. "

Fully agreed.

-

I'm a full on Cartesian substance dualist. That said, I'm not sure if that's because I'm ontologically committed to it or because I'm contrarian.

My basic fact is this: physics is objective. Consciousness is subjective. Therefore, consciousness isn't physics.

I believe quantum collapse is a simultaneous objective and subjective event, providing the link between the two.

Whether consciousness is truly a fully independent substance or not depends on whether it can carry out any calculations independently of the collapse; whether the collapse is a conduit or the thing entire.

"The particle in the cloud chamber obeys his predictions to a precision of, oh, 0.0000000000000000001."

You know, this is the real reason I hate many-worlds.

It is an attempt to excise true randomness from physics. Why can't physics be truly random? Not only can't I see any reason why not, there's a good reason to think it does have to be. (Blatantly pirated. The idea is that physics is fundamentally data-limited; an electron can only pin down so many of its degrees of freedom before it runs out of bits.)

Moreover, many-worlds cannot even get rid of apparent, empirical randomness, by definition, so I find it anti-science.

My link does depend on this randomness, so I may be more deeply committed to it than the data warrants, however.

I'm tempted to accuse it of being anti-consciousness as well. It's like many intuitively grasp that consciousness happens here and they're afraid of admitting it. (I observe this kind of overpowered but subconscious intuitive insight a lot, so it's plausible.)

"I have entertained the hypothesis that the world is just brutely illogical"

It's an empirically testable hypothesis. Perhaps, for example, general relativity and quantum mechanics are inherently irreconcilable. However, there's exactly no evidence for it at present.

"It's not clear to me how consonant that standpoint is with what Goedel said. "

I'm sufficiently certain I've disproven Goedel's first theorem, because self-referential sentences are logical fallacies. (They don't cash out to mean anything, in the end.)

(The second is just a generalization of the idea of begging the question.)

Peano arithmetic is essentially Turing-complete. Physics is Turing-complete. That Goedel's theories don't apply to weaker systems is not important.

Post a Comment